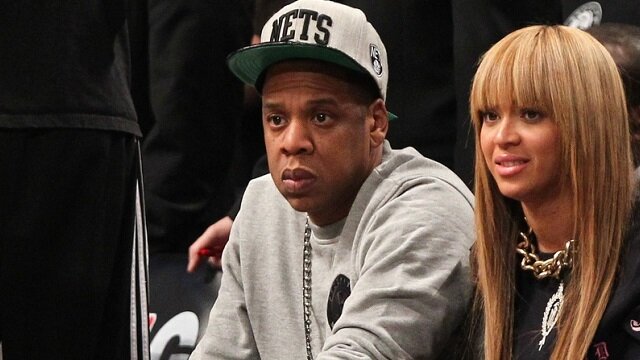

A Look at Jay Z, More Than an Icon

On the slick ‘97 track “Where I’m From”, Jay-Z kicks it off: “I’m from where the hammers rung, news cameras never come.”

Sixteen years later, you woud be hard pressed to find a news camera that wouldn’t follow Hov to Marcy, to Tribeca, to wherever he calls home nowadays. Given his high profile, it’s not very often that Mr. Carter obliges, which makes Elliott Wilson’s hour-long, two-part sit down with the man — that too in a hidden nook of Yankee Stadium — that much more special.

The two riff informally about music, moguldom, and more, but things really heat up five minutes into the second part when Jay-Z gets to talking about his Jerry Macguire act, his LeBron-Obama ties, and the Belafonte beef. Elliott Wilson is no Mike Wallace; yet he manages to elicit some thought-provoking responses from Jay-Z that shed light on the kinship bonds he has cultivated with elite athletes, speak to his rather haughty notion of charity, and raise questions regarding who and what he represents in his emerging role as a statesman. Let’s start in the sports world.

As recently as a month ago, Jay-Z gave up his stake in the Brooklyn Nets and became a licensed sports agent. Given his stature, Jay-Z quickly lured big-name superstars Robinson Cano of the New York Yankees and Kevin Durant of the Oklahoma City Thunder to his Roc Nation Sports agency, along with other prominent athletes. On his most recent album, “Magna Carta … Holy Grail”, Jay-Z announced that he’s gunning for the top spot occupied by Scott Boras, the man responsible for three of the four $200 million-plus deals in the history of the MLB.

In the interview, Elliott Wilson asks about his transition from Nets ownership to player representation. Citing the limited longevity of players’ careers and the widespread mismanagement of their salaries, Jay-Z paints himself as the savior, swaggering in the face of exploitative agents who have no regard for their clients’ well-being. Admittedly, it’s a salient image: uneducated baseball superstar gains acclaim, gets $90 million contract, then loses said money because the money-hungry agent has his hand stuffed too deep in the player’s pocket. It’s a common story. But is it reasonable? Are today’s agents really out to hustle their financially illiterate clients? I’m not so sure.

Agents build their careers on reputation. An agent who provides their client with improper information or tries to take advantage will be scrutinized, if not outright dismissed. Just ask Brian Overstreet, ex-agent of Tarell Brown, the 49ers cornerback who lost out on $2 million dollars because (supposedly) Overstreet failed to inform him of a “workout clause” in his contract that required Brown’s participation in official team workouts. Now that Overstreet’s name is tainted with this debacle — however proficient as he may be — players will be unlikely to seek out his services.

Scott Boras, who once represented current Roc Nation Sports client Robinson Cano, has been in the game for more than thirty years. With each new season, he attracts more and more players. Elite players seek out his services because of his reputation: he reliably and consistently secures multi-million dollar deals for his clients. If he pulled shady moved to take a bigger slice of the pie, what would happen to that reputation? Why would people still seek him out?

All this agent talk matters far less, of course, than Jay-Z’s account of why the players actually need him. His credibility, in terms of financial literacy and business sense, is undeniable. According to Forbes, Jay-Z’s net worth this year is $475 million. Thus, his argument goes, he can serve as a valuable resource for players looking to make mega-millions in their respective sports. As a business move, his Jerry Macguire act makes sense. But Jay-Z isn’t pitching his move as a business decision.

Instead, he points out irresponsibility by current agents, labels players’ inability to keep a handle on their fortunes “a travesty”, and presents himself as the disruptor. Roc Nation Sports, thus, is not simply about indulging Jay-Z’s passion for sports or increasing his brand or adding to his fortunes, but is instead an effort to advance “the culture”, to prop up his multi-millionaire counterparts who are being bamboozled out of what is due to them.

Without him, presumably, individuals will mismanage the millions and millions of dollars they make a year and, ultimately, will risk going broke. With his help, the era of irresponsibility will be over. The pockets of our most elite athletes will stay full and the rest of us will benefit from…what? The rich getting richer? More money in Jay’s pockets? A wider gap between the rich and the poor?

Look I don’t doubt that Jay-Z feels the pain (in the Clintonian sense) of superstar athletes whose funds run dry (early references to infamous money-blowers MC Hammer and Mike Tyson come to mind). And I don’t mean to write off the financial troubles of the wealthy as insignificant, but what Jay-Z sees as some kind of social responsibility really just comes off as a selective effort to lower the ladder to the affluent others that he can justifiably call his kin.

Okay so what? Is that really so wrong of him? After all, Jay-Z is simply lending a hand, right? Don’t other elites look out for their communities in the same way, albeit on a smaller scale? Okay sure. His agent act is warranted given his prominence and platform. But I cannot say the same for his underlying rationale.

Jay-Z is selling ice in the winter, fire in hell, water to a well; this time, however, he wants us to justify not his thug, but his statesmanship. Recognize his humanity. Acknowledge his social concern. Witness him stoop down and lift mankind up. He’s on the mound pitching himself to America, but those who know the old Jay-Z, who know his story, should be aware of the shift in his delivery and the softening of his command.

Nowhere is this clearer, perhaps, than in his treatment of LeBron James. Jay-Z’s first mention of LeBron in the Wilson interview hints at some financial wisdom he imparted “as a friend” earlier on in James’ career. His second mention shouts out the stark similarities of their stories: “Your dad left? My dad left too. Your mom’s name is Gloria? My mom’s name is Gloria too… Our stories is like the same thing.”

It’s a point well taken. Hip-hop artists and athletes certainly rise from the same ashes. R. Kelly and Benji Wilson came up on the same AAU basketball team on the Southside of Chicago. In Compton, young Kendrick saw Aaron Affalo as the one to follow. Metta World Peace can trace his steps back to the same Queensbridge streets that Nas, Lamar Odom, Prodigy, and Havoc walked on. In any case, there is little doubt that the narratives of athletes and hip-hop artists run parallel to one another. But Jay-Z bends the tracks, stretching the truth to create the image of a kinship bond between him and reigning King of the sports world.

LeBron’s upbringing was far from a bed of roses. Born to a teenage mother without a steady income, James lived nomadically for much of his childhood. During his pre-pubescent years, however, his mother Gloria entrusted his care to others — first a local football coach named Frank Walker and then to Dru Joyce II, his AAU basketball coach and friend’s father. Sports Illustrated magazine heralded LeBron as “the Chosen One” at age sixteen, media outlets rolled out the red carpet for him, and Nike signed him to a $90 million endorsement deal a month before his high school graduation. Every year since 2003, from the age of 18 till today, LeBron has taken in an eight figure salary. The upward mobility he has enjoyed follows a track — AAU to high school to NBA – that is shared by many NBA stars like Dwight Howard, Josh Smith and also Kevin Durant, Derrick Rose, and Kyrie Irving (if you account for the rule change preventing the leap from high school of course). Though the hype surrounding LeBron clearly surpassed anything the others had to deal with, his general storyline is not all that unusual (even the absent father and teenage mother for that matter).

Jay-Z’s age similarly informs his professional career. His 1996 debut album, the well-received classic Reasonable Doubt, barreled out of the Marcy Projects in Brooklyn when he was 26 years old. Think on that. Twenty-six years old. In an era where precocious MC’s reigned supreme. 2Pac: twenty at the time of 2pacalypse Now. Nas: the prodigy who went live at the BBQ at eighteen. And then we have Hov. Absent father. Check. Mother named Gloria. Check. Stable family home? Professionalized youth leagues to help hone his craft? Not so much.

The young Jay Z took his talents to the frontlines of the drug game. The street corner was his hardwood; crack cocaine was the rock; wins were stacks of green faces — Lincolns, Hamiltons, maybe some Jacksons on a good day; losses could be grim as the reaper; fiends were the closest thing to fans; teammates were neighborhood intimates who held their tongues; competing corner boys and po-po were the opponents; an even five-on-five match was a pipedream. He was a street hustler. Easily expendable. Readily replaceable.

In his twenties, still without the backing of a major label, Jay-Z found himself selling CD’s out of the back of his car. Then, tapping into the spirit that would come to define future endeavors, Jay hooked up with neighborhood buddies Damon Dash and Kareem Biggs and did for self. The result, Roc-A-Fella Records, became the platform for his hits. He built his name with chart-topping albums and a sharp business acumen that allowed him to stretch his arms well beyond the world of hip-hop.

Jay-Z and LeBron may have similar character traits, but it is odd for Jay-Z to promote the idea that their stories are “the same”. LeBron, born with tremendous natural athletic ability, groomed himself for success under the watchful eyes of nurturing adults. He even said in his most recent MVP speech that when his mother was around, she worked hard to ensure that his focus remained on basketball, not on putting food on the table or making ends meet. I do not mean to discount LeBron’s story. His ascent, especially in the face of overwrought critics and millions of megahertz of bright lights, is remarkable. But Jay-Z’s ascent is a rarity, if not a downright miracle.

Foot soldiers in the drug game are the pawns on the chessboard. The rank and file leadership in the drug industry has been known to keep unofficial insurance policies on their young infantry. As Sudhir Venkatesh and Steven Levitt detail in their work on the finances of a Chicago drug gang, families of fallen foot soldiers are generally compensated with $5000, equivalent to three years of salary. It’s the price to pay for the community’s silence and — to be frank with it — compliance. But the payment also tells you something about the lives of those serving on the frontline. Making it out unscathed, both physically and emotionally, is a challenge. Making it to twenty-one is an accomplishment. Making it to the driver’s seat of 300 Benz’s, the top of ten Billboard’s album-sales lists, and seats behind the President’s podium during his Inauguration? Only Hov.

It’s strange to think of Jay-Z playing down his proletariat beginnings and plopping himself in the same basket as “the Chosen One”. After all, he has branded himself as the embodiment of the American dream, the ultimate underdog. Why so sanguinely associate with someone whose struggles pale in comparison to his own? I don’t mean to suggest that Jay-Z is capitulating out of shame. Instead, I believe Jay-Z is conflating the privileges the two currently enjoy with the disadvantages the two faced in their distant pasts.

The two men are at the top of their respective worlds, racking on zeroes ahead of the decimal. Their fraternal bond comes primarily from the power and privilege they can enjoy with one another, not from having a mother with the same name and an estranged father. On one hand, Jay-Z, rather strategically, lends LeBron some street credibility here. It is not “My story is like LeBron’s” but instead “LeBron’s story is like mine”. It’s an important distinction, one that adds grit to LeBron’s working-class chops and positions him as more of a “self-made man” — the ultimate distinction for the self-indulgent. But let’s not forget that Hov is saddling up with the most marketable athlete on the planet. By saying his story is the “same” as LeBron’s, Jay-Z remains relevant with the prized younger generation who have elevated the four-time MVP and two-time champion to godlike status. Its no wonder that the most recent NBA video game had “Executive Produced by Jay-Z” printed in bold block letters all over the promotional material.

With this rather innocent bit of credibility swapping, Jay-Z reveals the same underlying motive present in providing financial literacy for athletes reigning in $10-20 million a year. Jay-Z is lowering the ladder to a fellow elite who benefits from ascending its rungs. In this instance, however, Jay-Z does a fair share of climbing as well. Central to his efforts to represent superstar athletes and treat them as family is a question he poses himself : He has an influence – what’s he going with it?

In August 2012, Harry Belafonte, the former entertainer and outspoken civil rights activist, spoke to that exact question. At the time, the 85-year old ex-actor was accepting an award at the Locarno Film Festival in Sweden. When put before the press, Belafonte responded, as always, with great aplomb. At times, his candor comes across as a virtue; other times it comes across as rancorous. The following exchange qualified as the latter:

Q: Are you happy with the image of members of minorities in Hollywood today?

A: Not at all. They have not told the history of our people, nothing of who we are. We are still looking. … And I think one of the great abuses of this modern time is that we should have had such high-profile artists, powerful celebrities. But they have turned their back on social responsibility. That goes for Jay-Z and Beyonce, for example. Give me Bruce Springsteen, and now you’re talking. I really think he is black.

To cut to the quick, Belafonte’s response could have been worded better. Calling Bruce Springsteen black directly after criticizing Jay-Z came off as a rebuke of Hov’s character more than a compliment to the Boss. But Belafonte, the man who picked out the suit Martin Luther King Jr. wore to his grave, speaks out of concern for his community, not out of spite. Belafonte intends, perhaps, to point to the way Springsteen paints portraits of the post-industrial pains of the working class. While Jay-Z does often settle for swaggering in the face of competitors and boasting of his Basquiat and Benz collections, we really can’t deny that Hov has had the gumption to speak out. Tracks like “Meet the Parents”, “D’evils”, “Regrets”, “Can I Live”, “99 Problems”, “Lost Ones”, have shown as much.

Perhaps, then, the trouble lies in the way he tells his story, the way he presents the stark realities of his life. Just listen to his response to a question Elliott Wilson poses about his notion of charity: “I don’t mean to sound arrogant but my presence is charity”. In other words, Jay-Z provides uplift simply by being himself. His story itself makes him a benefactor. He then proceeds to compare his effect on his community to President Obama’s, who, he implies, provided enough hope for African Americans simply by taking oath as the first Black President.

It’s a silly statement. An oversimplification that seemingly reduces Barack Obama’s agency to mere puppetry. But it also overlooks the two bestselling memoirs that the President penned prior to his election. Mr. Obama so saliently linked his life story to the nation’s story that millions of Americans switched on their screens to see him as the embodiment of hope. Jay-Z, in “Decoded” and through his music, hasn’t sold his story with nearly as much conviction.

But it is Jay-Z’s entire notion of charity that may be more troubling here. His claim that “his presence is charity” comes on the heels of his pitch to us that his work representing professional athletes is driven by a concern for their irresponsibility and his need to exert his influence. The contradiction here begs us to ask: for whom is Jay-Z’s presence alone a sufficient amount of charity?

And the answer, from his mouth at least, is the following: To ward off swarming agents and help multi-millionaire athletes avoid bankruptcy, Jay-Z’s presence is not enough. He has to get involved in the game. But to help anyone else who dreams of the kind of upward mobility he has enjoyed– likely the urban, Black poor — his presence is enough. All he has to do is maintain his presence.

Ultimately though, this isn’t even about Jay-Z failing to cater to Black America. I don’t know the exact statistics but I’d harken a guess that Jay-Z’s fan base is thoroughly diverse when it comes to race. Without a doubt, he is an American icon, not a African American icon or a Black icon. It’s foolish to vilify him for not doing enough for “Black America”. His songs cater to a far wider array of people and he has no duty to carry such a burden.

Jay-Z belongs to what Jelani Cobb calls the “richest class of exploited people in the world”. And it is within this context that we must confront the dilemma of who exactly Jay-Z the statesman represents. For what it’s worth, he seems to believe that he is playing for both sides: the exploited turned rich and the exploited who remain exploited. But while his sympathies may lie with both groups, his willingness to get in the field and combat irresponsibility head-on favors the first-generation wealthy, the elite athletes primed to join his ranks. Which leaves us to reckon with this: if his one percenter ties outweigh the sensibilities he shares with the other 99 percent can we still see him as the socially responsible statesman that he sees himself as?

For Belafonte, the answer is no. Jay-Z tells nothing of who we are, he says. Nothing of our history. Give me Springsteen, and now we’re talking: “My parents’ struggles, it’s the subject of my life…It’s the thing that eats at me and always will. My life took a very different course, but my life is an anomaly. Those wounds stay with you, and you turn them into a language and a purpose.” These words, taken from a recent New Yorker profile on Springsteen, give a glimpse of where Jay-Z may be lacking.

Other than alluding to his father’s heroin abuse and allowing his mother’s voice to grace the opening number on “The Black Album”, Jay-Z has hardly come clean on his parents’ struggles and any possible lasting effects. Circumstances out of his control have most certainly assisted in making his upward mobility possible, but I doubt Jay would ever shed his “self-made man” label to qualify his life story as “an anomaly”. And I would bet that Jay-Z could fill a million checkered composition books with boasts and slander before admitting to any wounds that have remained tender since his youth.

Maybe Belafonte had such an understanding in mind when he said that artists today like Jay-Z have told “nothing of who we are”, that they have “turned their back on social responsibility”. But Belafonte may have the wrong idea. Perhaps it’s just that Jay-Z has taken on social responsibility on his own terms.

As far as ex-street hustlers turned American icons go, he is the antithesis to Malcolm X; rather than redeem himself by lobbing bombs at the forces that pinned him down, he has blazed a trail through the burning house that has obstructed his path. And now he’s standing at the helm, in prime position to share the road map with his kinfolk. But who merits his regard? Those whose struggles make the Jay-Z story a possibility? Or those whose struggles have given Jay-Z the elite company he craves? Can he coherently cater to both?

The more poignant question — first posed by Jelani Cobb in his excellent study of the hip-hop aesthetic — is one that has haunted hip-hop for generations now. Will Jay-Z ever persuasively deal with human weakness and the ways in which the weak, the marginalized, and the exploited are able to flip the script — as he once did — and instill their lives with meaning?* And if the answer is yes, then, it seems, he will be regarded as the definitive hip-hop statesman, American statesman, whatever he wishes to be called. If that day comes, I will have to look back and wonder how I ever, ever had the gall to write an article knocking Jay-Z’s hustle. Until then, the jury is still out on Jay-Z the statesman.

Rohit Ghosh is a Senior Writer for www.Rantsports.com. Follow him on Twitter @RohitGhosh.

Paulina Gretzky: Top 20 Hot Photos From Instagram

Here's a look at the top 20 hot photos of new mom and Instagram queen, Paulina Gretzky. Read More

Pacquiao Trolls Mayweather On Twitter

Manny Pacquiao is so confident he can defeat Floyd Mayweather Jr. in the ring that he has started to troll him on Twitter. Read More

LRP: Mainstream Sports Media and Gambling

A look at the partnership between media and gambling, brought to you by Locker Room Picks. Read More

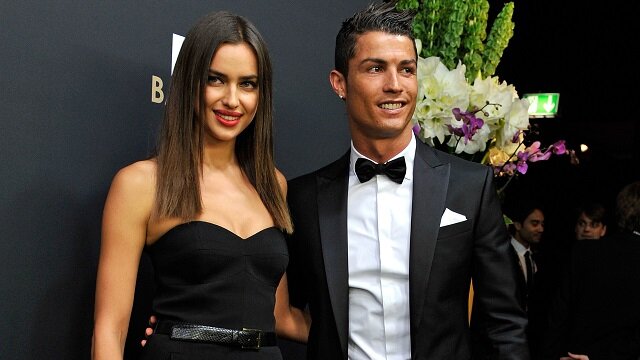

Hot Photos of Irina Shayk, Ex-GF of Ronaldo

With Irina Shayk back on the market after breaking up with Cristiano Ronaldo, here are 20 hot photos of the model to let the soccer player know what he'll be missing. Read More

Lindsey Vonn: 15 Hot Photos of Ski Racer

In honor of her making World Cup history, here's a look at 15 hot photos of ski racer Lindsey Vonn. Read More

LRP: Super Bowl Thoughts, Opening Line

Taking a look at the upcoming matchup in the Super Bowl and the opening line, brought to you by Locker Room Picks. Read More

20 Celebrity Seahawks and Patriots Fans

In honor of Super Bowl XLIX, here's a look at 20 celebrity fans of the Seattle Seahawks and New England Patriots. Read More

Seinfeld Sports References

Who doesn't love Seinfeld? In fact, it's one of the top sitcoms in India as well. Here are some sports references from the show. Read More

List of Indian Female Athletes

The following list is comprised of female Indian athletes who have either won championships, titles or medals, or set a record in their respective event. Read More

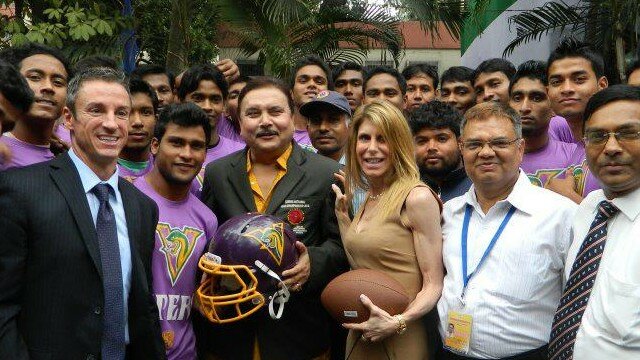

Learning from NFL's Blackout Policy

As the EFLI continues to grow, league management and fans can learn a great deal from the NFL's blackout policies. Read More

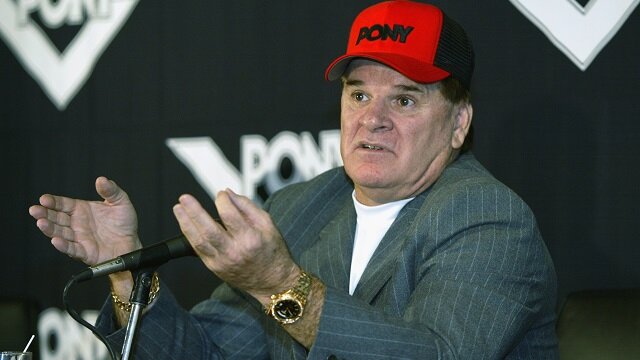

Rose's Ruin

Despite giving his life for the sport, Pete Rose is remembered for one mistake. Indian sports fans will find Rose's story to represent the struggle all athletes at one point or another deal with. Read More

Benji's Lessons

Sports fans and young athletes in India can learn a great deal about the harsh realities of life through Benji's story. Read More