What Young Indian Athletes Can Learn from “Benji”

I just got back from a brief trip to Chicago, Illinois where I spent the bulk of my time in the Hyde Park neighborhood on the South Side. As I strolled around, I was reminded of “Benji”, an installment of the ESPN 30 for 30 documentary series. Released about a year ago on April 20, 2012, this film covers a calamitous event that shook the South Side of Chicago in the mid-1980′s.

Directed by Coodie and Chike, “Benji” tells the story of Ben Wilson, a prodigiously gifted basketball player who took the city of Chicago by storm in 1984 by leading Simeon Vocational High School (now Career Academy) to its first ever State championship and being named as the top player in the 1985 class. Today, Simeon — with its four consecutive state titles — is a certified powerhouse. Nineteen years ago, it was hardly notable. Today, Simeon’s biggest star is Jabari Parker, a high school senior poised to be a one-and-done stud at Duke, with a big contract waiting in the NBA. Nineteen years ago, the legend of the South Side was Ben Wilson, an effervescent scorer whose life was tragically cut short when he became Chicago’s 669th murder victim in November 1984.

Much as they zoomed in and out of footage to showcase Kanye’s ups and down in the “Through the Wire” music video — albeit somewhat hastily — Coodie and Chike weave in and out of game footage, media coverage, animations, and interviews with his friends, family, and notable Chicagoans who have eluded early tragedy (Common, R. Kelly, Nick Anderson, Jesse Jackson, among others) to tell Benji’s tale. Directors for ESPN’s 30 for 30 series are rarely, if ever, A-listers and Oscar nominees. “Benji” is no exception. Outside of sportswriters’ tweets and sports bar banter, the themes of these documentaries are rarely, if ever, probed and picked apart. “Benji” is no exception. Yet something about the film’s treatment of the lacking resources in an inner-city neighborhood, the strength of the family matriarch, the spectacle of tragedy, and the psychology of the urban, teenage black male demands our collective attention and reckoning.

There is a tendency, I find, for intellectuals to detest sports writing and for sports junkies to dismiss academic thought. Academic types see sports fiends as too pedestrian, while the junkies find intellectuals to be too high brow. There should be an effort to join these two hands, to merge the sports world and academic world that are falsely perceived as so distinct from one another. The ideas I bring up here reflect my desire to do so. These ideas flow from my curiosity at the film’s relative lack of serious consideration, rather than from any desire to persuade you of my own perspective. Blurry as my vision gets, I hope to let you all peek into the lenses that hang over my eyes and judge for yourself what to make of Ben Wilson’s story.

–

Benji’s story starts and ends with Mary Wilson, his mother. A devoutly religious woman who worked as a nurse, Mary Wilson lorded over her children as a strict mother who inspired both fear and respect. Her older son, Curtis, helped raise Benji during long nights when night shifts kept Mary occupied. Somewhere along the way, however, Curtis fell into the ever-widening Reagan-era hole of crack cocaine abuse. Mary Wilson persisted, seemingly shedding some of her toughness onto Ben, whose relentless work ethic and competitive spirit fueled his meteoric rise.

For those familiar with the idea of a matrifocal community, the Mary Wilson character may come as no surprise. For those who still consider “Crash” to be a fair meditation on race — a camp I once belonged to — her character may be striking. In the 2005 film, Detective Graham Waters (Don Cheadle) fleetingly looks after his crack-riddled mother whose household mainstays include a rotten milk carton and a mangled tablespoon. As if the idea of an absent father isn’t enough, we’re also led to believe that Cheadle’s character has grown up and risen through the ranks without any sound maternal care. By highlighting the mother’s negligence, the narrative arc of the Detective’s wayward younger brother, Peter Waters, plays directly to the “crack baby” stereotype that pegs Peter as a strain on society who is disposed of by a man who feels threatened by him. The Waters family story may be a reality in some communities, but it’s hard to believe it’s anything but an exception rather than the norm.

The Wilson family story is also somewhat of an anomaly, but in a much different way. Mary Wilson’s composure in the aftermath of her son Ben’s death strikes a chord. Her ability to speak on behalf of her son with poise and power just hours after pulling the plug revealed a form of dignity that few women or men possess. There’s no doubt she was grieving. But she recognized that the sudden nature of the crime elevated the occasion to much more than just her own grief. Her public calm vaulted her to political acclaim as she gained favor with the Reverend Jesse Jackson, arguably the most powerful black leader of the day. She later took on a Eunetta Perkins-type role in Mayor Harold Washington’s political machine until he left office.

By aligning herself with Chicago’s Black political elite, Wilson raised her own profile and put a spotlight on the unjust circumstances circling over her son’s death. In 1985 in Chicago, all Emergency Response vehicles were mandated by law to take victims to the nearest hospital, not the nearest fully staffed hospital or the nearest trauma unit. As a result, Ben Wilson sat bleeding in an ill-equipped South Side hospital for hours before going into surgery. Nobody knows if a trauma unit would have saved Benji’s life, but the legitimacy of the law is clearly debatable.

Racial segregation post-Civil Rights era (even pre-) was carried out largely through city-led urban renewal and redevelopment efforts. The ghetto did not just pop up because poor people gathered in one area. It was built over time with steady doses of political pressure and weak resistance from the communities being affected. “Renewal” and “redevelopment” were simply euphemisms for segregation. As a result, Arnold Hirsch notes in Making the Second Ghetto, “The white hostility that isolated blacks spatially necessitated the creation of an ‘institutional ghetto’, a city within a city to serve them”.

A law that forces ambulances to take victims of violent crime in the South Side of Chicago to hospitals in the South Side only, regardless of the institution’s resources and staffing, speaks precisely to Hirsch’s point. A handful of neighborhoods, labeled publicly as “the ghetto”, become “a city within a city” where residents are caged in, receiving hand-me-down public services. The well-to-do doctors and other professionals flee to the suburbs, counting their blessings as they trot their way over. Ben Wilson’s story, in effect, may have been quite different if only he had lived elsewhere within the same Chicago city limits.

The laws have since changed. Mary Wilson scored a major victory by suing the hospital that was unable to resuscitate her son. In the aftermath of Ben’s death, her political prominence boosted her appeal. But Mary Wilson didn’t play her hand perfectly. By allowing her son’s death to bloom into a politicized tragedy, his funeral became a spectacle that alienated those who knew him best. The coverage of the funeral procession in “Benji” — a parade of free-flowing emotional gusto — shines light on the shallowness of the mob mentality.

Jam-packed with people who may or may not have ever even met Ben Wilson, the circus surrounding his last rites excluded those closest to him and, worse yet, promoted an exaggerated emotional response. A number of Wilson’s childhood friends saw the procession, perhaps rightly, as a contrivance. It wasn’t meant to honor their boy’s life. In their minds, the organizers had some ulterior motive, showcasing the community’s solidarity perhaps. The footage of hoards of wailing men and women highlights the high drama of the event.

I can see the logic of a mob assembling in response to someone’s death. Similar to a candlelight vigil for a missing person, it makes sense for an individual to decide to stand with their community in such a gathering. But the sadness circus is shallow. Whether you feel like it or not, you are expected to grieve. Whether you are teary-eyed or not, you are expected to be seen with droplets dribbling down your cheeks. Whether you are able to reel it in or not, you are encouraged to let loose in a space where hysteria has a certain healing power.

This idea of manufactured sadness lurks in the reactions of Ben Wilson’s friends. Perhaps they also felt violated in the way we sometimes do when our good friends start to spend more time with new friends that they have made. Others were being shown on the TV screen; others were giving eulogies for the dude they thought they knew best. Death is a tricky beast, one we rarely confront because of the inevitable uneasiness associated with it. Yet death’s inevitability gnaws at us, particularly when we remember those we know who became its prey.

Ben Wilson’s death, the 669th of the year in Chicago, sent shockwaves across the city. The police quickly nabbed the two adolescent assailants, 15 year-old Omar Dixon and 16 year-old Billy Moore. The media jumped on the story, hastily labeling the perpetrators as “members of a street gang” and “gang members”. Moore and Dixon signed statements at the police station acknowledging the crime was a “mugging followed by a cold-blooded shooting”. They accepted charges of Armed Robbery and Murder, but later recanted their statements, intimating that they were pressured to accept the story.

An interview with Billy Moore, recipient of a 2009 White House award for exemplary rehabilitation, gives us a glimpse of reality, or at least another version of reality. There are reasons not to believe Billy’s side of the story. He is a convicted murderer, as he readily admits. There is no definitive evidence to back him, simply hearsay from witnesses and participants. Yet I find his version of the story to be much more compelling. It’s not hard to see how Chicago police officers could have coaxed a confession out of two teenagers. It’s even easier to understand why Billy Moore might have acted the way he says he did in the heat of the moment on a cold afternoon in November 1984.

That morning — fourteen months after the premature death of his father — Billy Moore tucked a gun in his pants and headed to Simeon to settle a petty beef involving his cousin and some stolen cash. By the time he got there, the issue was settled. As Moore and Omar Dixon waited for a friend named Erica outside a nearby sandwich shop, Ben Wilson, locked in an argument with his girlfriend Jetan Rush, walked past and shoved Moore. A confrontation ensued. Moore demanded an apology, but the 6’7 seventeen-year old had no intention of backing down. When Moore showed the gun, Wilson snickered, “What? You gonna shoot me?” Two shots later, Moore was on the run while Wilson grappled with the two bullets lodged in his torso.

This was a dispute over pride, over reputation. Moore felt disrespected and Wilson knew better than to surrender his agency. This inability to accept slander of any kind is what makes Marlo yell out “My name is my name!” in the fifth season of The Wire. For a teenage male, particularly in an urban environment where individualism is more readily internalized as the only guiding principle, reputation carries weight and it must be protected at all costs.

Billy Moore learned this lesson as a ten year-old when his grandfather told him while cleaning his own gun, “Don’t you ever pull a gun on somebody and don’t use it”. As he stood six years later — gun in hand — before the top basketball prospect in the nation, the old head’s words echoed in his brain. Now you could go all Daniel Patrick Moynihan here and yap on and on about immoral family values and yada yada yada. But take a second to consider the logic: If you don’t want to be a tough guy, don’t act tough. If you do want the reputation, know that being a fake tough guy (coincidentally the same the three words KD directed at Chris Bosh) is akin to being a punk. Thus, taking on a tough guy persona means being willing to do what it takes to take to back that resolve. I don’t mean to suggest this is sensible advice, but it is logical. It is also deeply flawed, a reality Billy Moore swiftly understood only after it sunk in that he was responsible for a human being’s death.

I can’t help but imagine how this story and countless other similarly staged standoffs would be different if there wasn’t a gun playing a leading role. In upscale and squalid neighborhoods alike, children vie for attention, importance, and recognition. Competitiveness is stitched into the fabric of American society. Squabbles among males are commonplace in schools. Words are exchanged, bold claims are leveled, and, at times, fists prevail over cooler minds. Fighting is not inherently wrong.

Fistfights — I must rely on others’ stories here because I have little experience outside of brotherly bashes — can certainly be transformational, exposing us to our weaknesses and starkly reminding us to build up a stronger self. Fights can also be belittling and miserable, but by prodding us into a time of challenge and controversy it has the potential to reveal the true measure of ourselves (Side note: I feel awfully awkward bringing in the words of Dr. Martin Luther King while defending fistfights but that’s just how it makes sense to me right now). Fighting with guns, on the other hand, only exposes us to a world of regret and everlasting pain. Being the perpetrator guarantees a stint behind ironclad bars or perhaps psychological torture; being the victim all but insures a long kiss goodnight.

Yet still current newspaper headlines detail the efforts of a gun lobby to push more guns into schools “to protect the students”. Chicago still has upwards of 500 homicides a year. The Chicago Police Department seizes six times as many guns as the NYPD. This is hardly a political issue we should toss around like it’s a hot potato; this is a public health travesty that has been festering for decades (get educated here).

–

“Benji” consciously levels many of the claims I’ve made here, but it also deflects them. It isn’t a film that tells us to confront the problem of guns on the street the way global warming was presented in “An Inconvenient Truth”. It doesn’t beg for our sympathy for the urban youth of Chicago as “Invisible Children” did for Ugandan children soldiers. It is intended for a sports-centric audience (see what I did there?). An audience that responds to the hyper-competitive/relentless work ethic narrative and, of course, the predominant narrative in sports tragedy — a dream unfulfilled. Those who saw Benji play were taken by his electric charm. Those who he held sway over knew him as “Magic [Johnson] with a jump shot”, a statement that stands only as an epitaph today.

By satiating the sports fan’s story-hungry psyche, “Benji” succeeds. But the film reveals so much more about the 80′s-era realities of inner-city life that it would be a shame to watch and to not think, to not discuss, and, perhaps most importantly, to not be curious.

Rohit Ghosh is a Senior Writer for www.Rantsports.com. Follow him on Twitter @RohitGhosh.

Paulina Gretzky: Top 20 Hot Photos From Instagram

Here's a look at the top 20 hot photos of new mom and Instagram queen, Paulina Gretzky. Read More

Pacquiao Trolls Mayweather On Twitter

Manny Pacquiao is so confident he can defeat Floyd Mayweather Jr. in the ring that he has started to troll him on Twitter. Read More

LRP: Mainstream Sports Media and Gambling

A look at the partnership between media and gambling, brought to you by Locker Room Picks. Read More

Hot Photos of Irina Shayk, Ex-GF of Ronaldo

With Irina Shayk back on the market after breaking up with Cristiano Ronaldo, here are 20 hot photos of the model to let the soccer player know what he'll be missing. Read More

Lindsey Vonn: 15 Hot Photos of Ski Racer

In honor of her making World Cup history, here's a look at 15 hot photos of ski racer Lindsey Vonn. Read More

LRP: Super Bowl Thoughts, Opening Line

Taking a look at the upcoming matchup in the Super Bowl and the opening line, brought to you by Locker Room Picks. Read More

20 Celebrity Seahawks and Patriots Fans

In honor of Super Bowl XLIX, here's a look at 20 celebrity fans of the Seattle Seahawks and New England Patriots. Read More

Seinfeld Sports References

Who doesn't love Seinfeld? In fact, it's one of the top sitcoms in India as well. Here are some sports references from the show. Read More

List of Indian Female Athletes

The following list is comprised of female Indian athletes who have either won championships, titles or medals, or set a record in their respective event. Read More

Learning from NFL's Blackout Policy

As the EFLI continues to grow, league management and fans can learn a great deal from the NFL's blackout policies. Read More

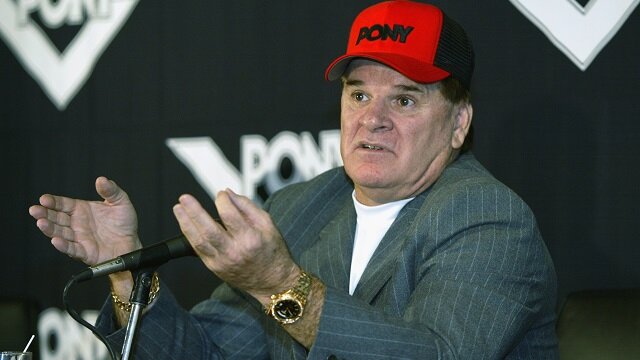

Rose's Ruin

Despite giving his life for the sport, Pete Rose is remembered for one mistake. Indian sports fans will find Rose's story to represent the struggle all athletes at one point or another deal with. Read More

Impact of Jay-Z

Fans in India may know Jay Z, but cannot comprehend the impact he has on the sports world internationally. Read More